As part of the Social Microbes residencies, Hat Porter joined us to work for 2 weeks, collaborating with Dr. Elze Hesse, and with the Fish Factory as an extra host. So that more people can see their work, below are photos and the text content of a zine that they made - this was all exhibited at the Fish Factory in June 2023. The residencies have been funded via Elze Hesse's UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship.

Hat's work explores autistic people's priorities for research, in the context of research on gut microbes and autism. As is common with academic research, the people who it is for and who are directly affected by the research are largely left out of the conversation, and don't have power to drive the research directions. This harms the research itself, and the people who are supposed to benefit from it. There are lessons in here for researchers from all disciplines on all topics. One thing that stood out to us was Hat's experiences hand stitching the quotes from autistic participants - Hat spoke of the slowness of the process giving time to really think about what each individual person had said - spending around an hour with each sentence. Again this time and deep care for the people involved is something that is sadly missing from the fast-paced publish-or-perish culture of research.

Photo of Hat at their residency exhibition, by Jas

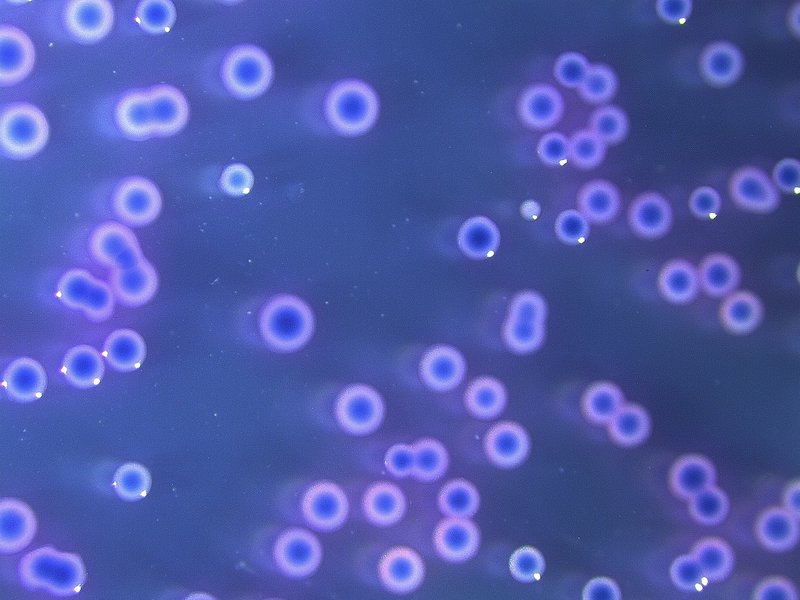

Photos of Hat's own gut microbes, grown in the lab

These were printed onto sheer fabric for display, also seen in the photo of Hat at the top of this page.

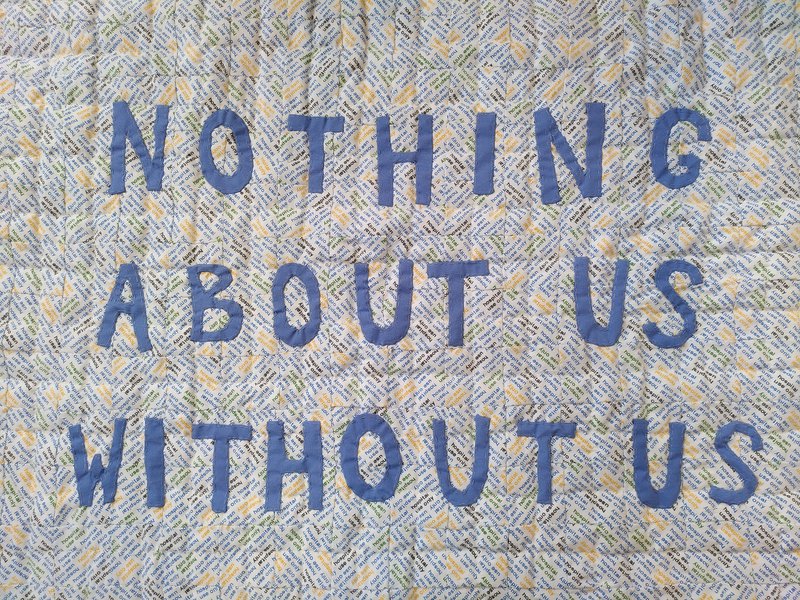

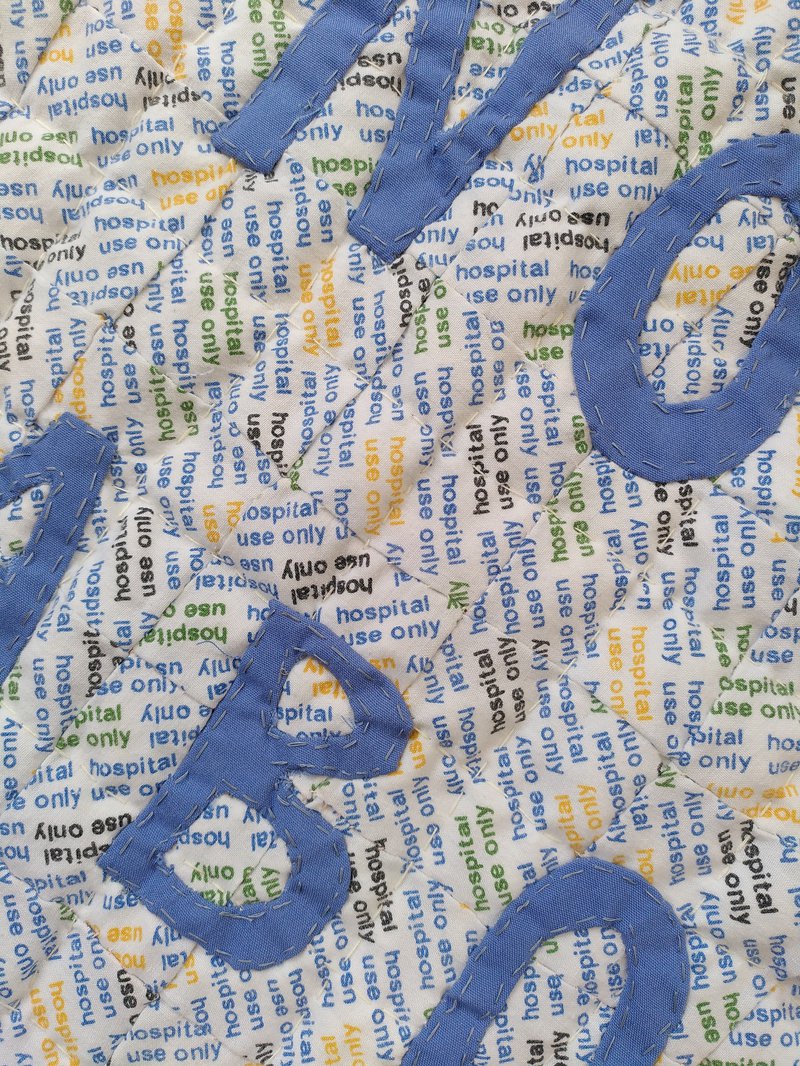

Quilt made from hospital pyjamas and scrubs

Microscope slides with fabric microbes

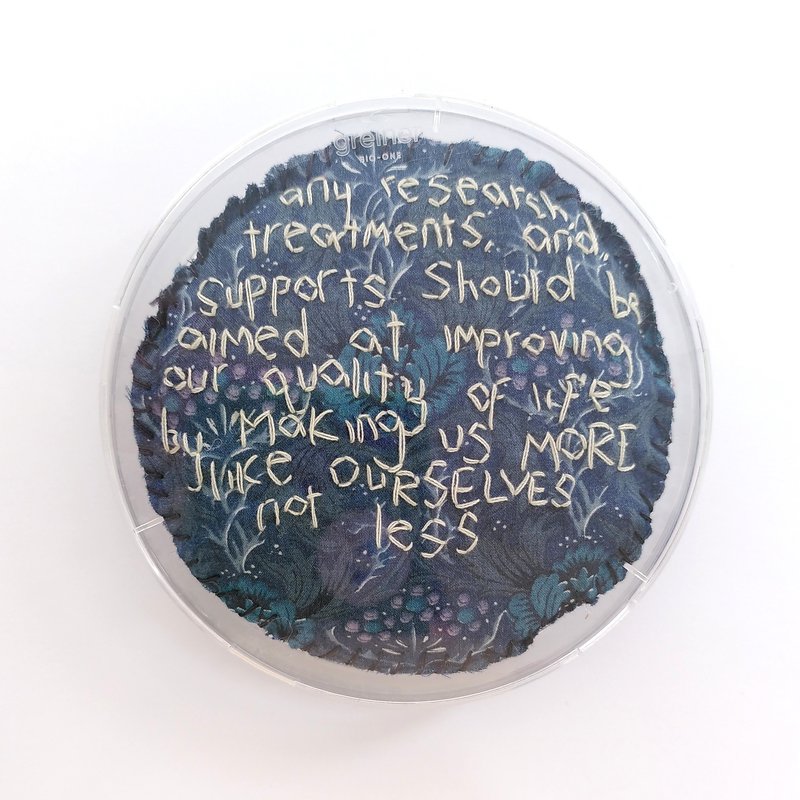

Petri dishes with hand stitched quotes from autistic participants

You'll find more context for these in Hat's zine text below. Here are the quotes that are stitched, numbered from left to right and top row to bottom row.

- They without any doubt state that autists have poor communication skills… if that’s already one of their main research “facts” the whole research isn’t valid.

- On the one hand I am interested as finding out new things about the body is always exciting but I do not like the lens in which it is being done.

- There are so many other aspects of our lives that are by far more worthwhile studying.

- I think it would be quite beautiful to see on a cellular level how my autistic body responds to the world however if research tries to eradicate my existence then I do not support it.

- It feels negative and like it is cure focused rather than focused on helping autistic people live our lives.

- I want to be autistic, I love my neurodiversity.

- It feels like with anything like this there’s a possible slippery slope to ideas about ‘curing’ autism.

- I feel like if money is being spent on research related to autism it could be better spent elsewhere.

- I don’t really feel that it’s relevant to me but I find the research very interesting and I know it is important to some people.

- I was not aware of this research but reading about it I couldn’t help but feel bothered by the view of autism as a curable pathological condition.

- It feels aligned with research looking for a cause/cure for autism – I would so much rather research focused on the ways the world doesn’t accommodate us.

- How much is research aiming to “fix” rather than actually help autistic individuals.

- We are not something that needs to be fixed we are not the problem. We are whole as we are and do not need treatment.

- How can autistic individuals be accommodated to reduce their daily stress so they do not suffer from intestinal problems.

- I think autism should not be viewed in a pathological way, and any research, treatments and supports should be aimed at improving our quality of life by making us feel MORE like OURSELVES, not less.

- A lot of autistic people have gastrointestinal issues – I would like to see more aftercare with diagnosis.

- Research should be more about how to help us living our lives.

- We need trauma focused therapy adapted for us as so much of our lives are spent trying to fit in at the expense of our own needs.

Social Microbes: art, autism, and gut microbes - a research zine by Hat Porter

This zine is produced during my artist residency with Then Try This and The Fish Factory, in May and June 2023 on the theme of ‘social microbes’. The residency is funded through Dr Elze Hesse’s UKRI (UK Research and Innovation) Future Leaders fellowship, hosted by Exeter University.

Through this residency I have looked at research about autism and gut microbes and considered this in the context of wider issues within autism research as a discipline and autistic people’s priorities for autism research.

I asked autistic people 2 questions about this topic. Their responses are included in this zine. I also made artwork in response to what people shared. I also grew and photographed my own (autistic) gut microbes!

This zine is created as part of an art exhibition at The Fish Factory, Penryn. The show includes artworks, an academic paper and this zine, exploring the themes of autism and gut microbes and considering creative ways of disseminating research.

What has the gut got to do with autism?

The human gut microbiota is the many microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi and viruses which live in the gut. These are generally harmless and play important roles in digestion, for example by breaking down non-digestible substances. However, imbalances in the numbers and types of microorganisms in the gut (too many of some and not enough of others) may impact the relationship between the gut and the brain. Researchers are interested in this link and the implications it may have for better understanding links between the body and mental health.

Over the past 2 decades, there has been significant rise in research which looks to see if there is a link between microorganisms in the gut and autism. Some research looks at if autistic people have different microbes in the gut compared to non-autistic people and if this may help us to better understand the needs of autistic people with gastro-intestinal issues or conditions. However, other research is more focused on how differences in autistic people’s gut microbes, compared to non-autistic people’s, may actually have a role in what makes people autistic. This leads to others considering the possibility that if specific patterns of gut microbes lead to autism, whether by altering these an individual’s autism can also be altered. For example, by looking at if autistic people's behaviour changes when they are given a 'treatment' such as antibiotics, probiotics (live microorganisms taken to benefit your body), faecal transplant (where a donor's faeces is put into the gut to introduce healthy bacteria) or following specific diets. Some research looks at mice and rats and considers how this may relate to humans.

Although some studies find a correlation (a link between the variables) between autism and gut microbes, it is difficult to tell whether something about gut microorganisms causes autism or whether a link is related to something else like diet. There is also vast variation in the results of these studies, and some haven’t found any differences in the gut bacteria between autistic and non-autistic people. There are also limitations on research based on rodents (not least in relation to the ethics of subjecting animals to experimentation). For example, one study looked at putting microbes from human autistic participants into pregnant mice to observe the behaviours of their offspring. Although the research found differences in how the offspring behaved compared to ‘typical’ mice, it’s not possible (or helpful) to apply this to humans.

Some people think this research is really important and will help us to understand autism better. Other people worry this research views autistic people negatively and rather than viewing autism as a positive aspect of a person, it considers autism as a disease and used negative words and phrases through the write up of the research which demonstrates the negative attitudes the researchers may have towards autistic people for example in suggesting autistic people would benefit from being less autistic.

Research standpoints

Research is influenced by research standpoints which are the theories, perspective and assumptions which underpin research and influence how this is conducted. In this case, it may be about how someone views and defines autism; these definitions can differ significantly. Often, autistic people favour a neurodiversity model of autism which views autism, not as a disease or a disorder, but as natural variation in how people’s brains work and see this is a positive thing. The neurodiversity model recognises autistic people often experience difficulties which are made worse by our society being built in a way which doesn’t support us. Contrastingly, some people may see autism as a disorder and consider it something to negatively impact the person. They may support looking for treatments or cures to change how autistic people’s brains work.

The neurodiversity model of autism isn’t only about how people’s minds or brains are different but also about how this impacts people’s bodies. This is because the brain and body are inseparable and each influence one another so any differences in the brain will also manifest in the body. Therefore, research looking at differences in autistic people’s gut microbes may help to understand the ways autism isn’t just about the brain but about the body too. This may also be important because autistic people are often more likely than non-autistic people to have problems with their digestive systems so understanding this more could help to give better support to autistic people. However, this is often not the perspective this research takes, and the researchers may hold a more medicalised idea of autism as a disease or disorder.

These differences in how people view autism impact how they may think about the challenges autistic people face, for example if someone is experiencing extreme distress, a medical model may look at things internal to the autistic person and how these may cause their distress (for example the microbes in their gut or their genes) while a neurodiversity model may consider the distress to relate to how the autistic person’s brain works but look more at external things (for example how environments can overwhelm the person’s senses or how being misunderstood by those around them can make communication difficult). Autistic advocates and campaigners argue the medical model views autistic people negatively and can prevent research looking more at how environments impact autistic people.

The differences in how researchers view autism impacts their research at every stage from identifying priorities, planning research, conducting it and interpreting and communicating the findings. This means research will always be influenced by the social and cultural values of the researchers and the wider contexts the research is conducted in. However, this is often overlooked as a limitation of medicalised research. Autistic researchers, Botha and Cage (2022) asked autism researchers about how they view autism research and categorised their responses by the language used. They found those who used more medicalised language to speak about autism also used more terms which dehumanised, objectified and stigmatised autistic people. Autism researchers must acknowledge and consider how these attitudes translate into how they conduct their research.

Research aims

One way a research team’s underpinning attitudes may show in research is through what the research aims to achieve. With much of the research looking at autism and gut microbiomes there is an aim to explore whether it’s possible to change autistic people’s behaviour through changing something about their gut microbes. This approach to finding a ‘treatment’ for autism requires a definition of what would be considered a positive outcome. For example, a study by Zhu and colleagues (2023) said “our results indicate that FMT [faecal microbiota transplantation] can benefit children with autism by reducing ABC [Autism Behaviour Checklist] and CARS [Childhood Autism Rating Scale] scores”. By indicating they think showing fewer autistic traits automatically benefits autistic children, they show a bias here. A treatment which makes an autistic person appear less autistic can only be considered successful if you view being autistic is a negative thing. It also shows a view that autism is something which can be changed, rather than an inherent part of how someone’s brain works.

What do autistic people want from autism research?

Although there is lots of research about gut microbes and autism, there isn't very much discussion with autistic people about what they think of this research and how important, useful and acceptable they think it is. When autistic people (as well as autism researchers, allies and families) have been asked what they think is the most important thing for autism research to study they have said they want research which has a real-world impact for them such as how public services can meet autistic people’s needs better and support autistic people’s mental health. The lowest priorities identified were about the prevalence of autism, causes of autism (such as genetic, biological and environmental factors) and treatments for autism. In fact, many autistic people oppose research being done around causes and treatments for autism considering this to harm autistic people.

Although research around support for autistic people and social issues such as policy and challenges autistic people face were identified as the highest priorities for autism research to look at, these were actually the areas which received the least funding. Research on biology, treatments and causes of autism had the most funding – the opposite of the priorities autistic people have shared. Additionally, autism researchers often focus on children rather than autistic adults and lack diversity in the samples of people they engage with meaning even when autistic people’s voices are heard in research, it is not representative of the wider community.

Autism research should benefit autistic people

The differences between where autism research funding goes and where autistic people want it to go is part of wider issues in how society views autistic people and the injustices autistic people face but also could be argued to contribute to these harms. For autism research to really serve autistic people as the subjects of their research there needs to be greater alignment of the values, views and priorities of autistic people but to be able to do this, researchers need to be speaking to autistic people in the first place to know what matters to us.

Research is often conducted on autistic people rather than with us. This means autistic people may be involved but as participants and they may just be represented through data such as data about their gut microbes and scores on assessments. Instead, participatory research works with autistic people (and is often led by autistic people) viewing them as partners and ensuring they have input and involvement in the research. This type of research is beneficial for the autistic participants and the researchers and can help to broaden what we know about autism and about how autistic people experience the world. Research also needs to be involving autistic people at every stage of the process including deciding what to research and what questions need to be answered, conducting the research and analysing and sharing the research.

Research outcomes

Because research about autism and gut microbes doesn’t match what autistic people say is their priority for research and describes autistic people in ways which may be considered offensive and harmful, it could be questioned if the research contributes positively towards the autistic community. Research can have implications including leading to new focuses on research, new ideas, new policies, changes to how people are supported or impacting how the public think about a topic. Some of the impacts research has can be different to what the researchers hoped or intended before publishing. Therefore, it is essential for researcher to consider, and clearly state, the possible implications of research and ensure this is responsible and ethical. When looking at topics such as how autistic people’s gut microbes may differ from non-autistic people’s this can influence how people think about autistic people and may consider ways of trying to treat or cure autism.

There’s been a long history of autistic people being treated with violent ways of trying to stop them being autistic, and even the mass killing of autistic people as part of Nazi eugenics. Eugenics describes the promotion or practice of seeking to ‘improve’ the human species through selectively breeding traits considered ‘desirable’ and/or seeking to remove or reduce births (through a variety of unpleasant means) individual with traits considered ‘undesirable’. Many autistic people worry research which looks for ways of identifying and treating autism has motives or implications of being able to screen before birth for autism (and subsequently, people may consider termination) or prevent autistic people from being born in other ways.

Research which looks at ways of treating or changing autistic people also raises questions about which parts they are trying to change given autistic people are also hugely different and different traits can be valuable, beautiful and also just neutral depending on the context and who we are considering the traits as impacting. Trying to make a hierarchy of what is and isn’t valuable raises questions about whom these traits impact or challenge: the person themselves or those around them and needs addressing. This risks further falling into a way of only valuing autistic people because of their supposed contribution to society rather than inherently valuing us as human beings with human rights.

What do autistic people think of research about gut microbes and autism?

I asked autistic people two questions about what they think of research about the gut microbiota and autism and what their priorities for autism research are. Respondents were only asked 2 questions and I didn’t ask information about gender, ethnicity, age or other characteristics. 12 people responded, I will discuss what they shared.

Question 1: How do you, as an autistic person, view research about microbes and autism?

Interest in expanding knowledge about autistic bodies

Some respondents said they were interested in research about autism and gut microbes because they are interested in the human body. One person shared they were specifically interested in how their autistic body interacts with the world. They shared, “I think it would be quite beautiful to me to see on a cellular level how my autistic body processes and responds to the world I interact with and my experiences”. Some respondents also shared awareness the research may be useful for autistic people who have digestive sensitivities, “well, a lot of autistic people have gastrointestinal issues - I would love to see more aftercare with diagnosis eg - let’s see how your gut is and if there is anything we can do to support your co-morbid issues”. One respondent also discussed this in the context of their own experiences, noticing a link between their autistic experiences and how their digestive system functions: “as an autistic person, I find I am very sensitive to the world around me and often find that there seems to be a link between how well I am feeling and how well my digestive system is functioning”.

These responses describe considerations of the differences in how autistic people’s bodies may function compared to non-autistic people’s and sensing research is therefore useful in better understanding these experiences.

Concerns about how autistic people are viewed in the research

However, respondents also expressed concerns about the approach of the research and the underpinning assumptions of the authors. One person said, “What is very worrysome to me, is how they without any doubt state, that autists have poor communication skills… If that's already one of their main research "facts", the whole research isn't valid”. Therefore, it wasn’t necessarily the research subject itself the respondents disagreed with, but the way it is approached. This was highlighted in one response which showed a mix of feelings about the research, “on 1 hand I am interested as finding out new things about the body is always exciting but I do not like the lens in which is being done”. One respondent expressed questions about how autistic people’s bodies are viewed in such research, questioning why non-autistic bodies would automatically be viewed as superior to autistic people’s “Do autistic people have a lack of microbes, or a different landscape of microbes? Are non-autistic guts simply assumed to be better?”.

These responses show respondents have a mix of feelings towards this research and also highlights their value they place on understanding the underpinning assumptions of researchers and ensuring research is approached in a way which reflects positive ways of viewing autism and holds relevance to autistic people’s understanding of their experiences. This was further emphasised by one respondent who suggested the research intentions and assumptions should be made explicit to support research to better serve autistic people “I think that the ethics and intentions for this research needs to be clearly documented so that any findings are only applied in ways that empower and protect autistic people”.

Opposition of research which seeks to find a ‘treatment’ for autism

In particular, respondents were concerned about the potential for the research to lead to consideration of “treatment” or “cure” for autism, which was opposed and presented as, without question, a negative thing. For example, one person shared, “I also feel like it focuses too much on biological factors related to autism and it feels like with anything like this there's a possible slippery slope to ideas about 'curing' autism”, whilst another shared, “This doesn’t feel helpful to my lived experience, at all. Like, what’s the end goal of this research? To alter autistic behavior? No thanks!”. Another respondent’s concerns extended to thinking about the wider, longer-term implications of research which may consider ‘treatments’ and ‘cures’ for autism, they shared, “feels very much like find source of autism to treat/cure. I feel it will lead to the potential of testing for autism before birth and people terminating pregnancy because of it, so like eugenics”.

These responses perhaps suggest an anxiety amongst the respondents about the aims of research on autism and gut microbes; a nervousness which likely stems from the harmful research which perpetuates negative ideas about autism, this may include studies looking at autism and gut microbes but is not limited to this.

With resistance to the idea of ‘treatments’ or ‘cures’ for autistic people, respondents expressed love and pride related to their identities, they not only didn’t want ‘treatments’ for autism but celebrated their autism: “I don't want to be less autistic and I don't feel like I want to do things that make me work differently - I want a world which better accommodates me as I am”. Another respondent shared, "I want to be autistic, I love my neurodiversity, I love other autistics and neurodiverse people”. Through emphasising their autistic pride, these respondents questioned any research which aimed to change aspects of autistic identity, feeling this is not relevant to them and doesn’t match their priorities.

Additionally, respondents also expressed concerns about research on autism and gut microbes receiving funding at the expense of other areas, “I feel like if money is being spent on research related to autism it could be better spent elsewhere” and “There are so many other aspects of our lives that are by far more worthwhile studying”.

Question 2: As an autistic person, what do you think are the most (and least) important things for research about autism and autistic people to focus on?

Autism and physical health

Some respondents were interested in research about autistic people’s physical health, for example one person shared, “I'm really interested in the research about other issues (physical and mental) associated with being neurodivergent”. Another respondent described interest in research about autism and gut health in the context of digestive issues, “It would be fantastic if research could focus on how to best support autistic people by finding out how diet (next to sleep and everyday events) could be best tuned to their needs and help them be as rested and balanced as possible. I think this reduces not autism but the struggles autism can cause a person”. These responses reflect considerations of autistic people’s experiences as related to the brain and the body and identifying value in research which seeks to develop understanding of the divergence of autistic people’s bodies and how any struggles associated with this could be supported.

Research that isn’t about autism but is about autistic people’s experiences

Other respondents expressed they would prioritise research which focuses on supporting autistic people in their daily lives and has tangible impacts. For example, one person shared they prioritise research about “what would make life easier, development of accessible tools and practices to make environments more welcoming to autistic people”. Another respondent shared similar preferences and acknowledged the wider environments which may create challenges for autistic people, “I think it should focus on making our daily lives easier by focusing on ableist structural and social forces that make life harder for us”. These respondents indicated more interest in research on things which are external to autistic people, rather than about the biology or internal make up of the autistic people; this is less about what makes people autistic and more about the external influences which causes autistic people distress.

This was also reflected in other responses which expressed a desire for research which considers how to support autistic people in the context of distress experienced. For one respondent, this was considered in the context of the stress and trauma autistic people experience in navigating ‘fitting in’ in contexts which don’t support their needs, “We need trauma focused therapy adapted for us as so much of our lives are spent trying to fit in at the expense of our own needs”. Respondents also wanted to better understand the expereinces of discrimination autistic people face and how this impacts health, for example, “The most important would be how society views us, we are not deficient in anything but the understanding from ableds”. Another respondent shared they wanted research focused on the harms autistic people may face in care settings, “research quality of training provided for staff in autistic residential homes and educational settings as well as investigate abuse incidences by these staff members”.

Opposition to autism ‘treatments’

Similar to the comments shared in response to the first question, respondents described considering research which looks at treatments from autism as not being important to them, “Least important research areas… any tests that try to diagnose or ‘cure’ someone before they are born, medications that seek only to make someone appear more neurotypical”. Another respondent was clear in stating they viewed attempts to change autistic people or cure autism as eugenics, “research about autism and autistic people needs to focus on helping us succeed in an ableist society, not focus on "curing" autism which is eugenics”. Furthermore, another respondent described “I don't believe that the goal should be to turn us into a closer approximation of a non-autistic person, and erase the essence and beauty and fullness of who we are”, as discussed above autistic pride was emphasised to counter any suggestion of ‘curing’ autism; these respondents described opposing ‘treatments’ for autism both due to ethical questions this may raise, but also through a love of being autistic. Indeed, the positive aspects and joy of autistic experiences was highlighted by some respondents as a priority for autism research, this included “I want to see science done around what strengths we often have, like about our sensory differences” and “about [our] joy and pleasure and community!”

It's not only the research topics which matter, but also how it is conducted

Respondents also expressed preference for research to be led by autistic people “for autistic people to be leading the research. It’s so behind because we don’t have a voice in the conversation”. In describing autism research as “so behind” due to the absence of autistic voices in research, this response implies an absence of inclusion of autistic people in research is not only negative due to exclusion of the person the research is about, but that this also negatively impacts the quality or impact of autism research. Another respondent also expressed the importance of ensuring diversity amongst researchers “any research about autism should be being done by autistic people - and not just white men, either. Autism research if it's happening at all needs to be far more intersectional”. In appearing to suggest no autism research would be better than research which is not autistic-led and intersectional with the phrase “if it’s happening at all”, this respondent emphasises autistic involvement in research as not just valuable but absolutely essential.

Conclusions

The responses to these two questions indicate autistic people had a mix of feelings about autism research looking at gut microbes with both some strong criticisms of research looking at microbe based ‘treatments’ and ‘cures’ for autism but also interest expressed in understanding how autistic people’s bodies work and how such understanding could also benefit in supporting autistic people with any difficulties they face. The responses suggested, at least from some autistic people, there is a level of interest in research about autism and gut microbes but some anxiety and nervousness about the underpinning assumptions and approaches of this research and its potential implications. Whilst some respondents felt research about physical health of autistic people is important, many also shared having greater priority for research which looks more at external environments and how this influences autistic people’s experiences and wellbeing. Finally, many respondents viewed being autistic as a beautiful, positive and joyful thing and shared their pride in their identity to counter suggestions and ideas that this is something which could – or should – be treated.

This was a small scale, informal survey but the responses indicate autistic people may have strong views about research on gut microbes and autism which should be considered before expanding research on this area.

By Hat Porter, June 2023

With thanks to Then Try This, The Fish Factory and Dr Elze Hesse for support through this residency which was funded through UKRI.