We have begun a new project with Dr. Ben Ashby (University of Bath) to help with the public engagement for his research. Ben’s work is a bit like being an ecologist of the microbial world – considering how the landscape and communities of creatures living there move around, interact, and affect each other in various ways. He’s particularly interested in how complicated ecosystems and communities of species and individuals might change how pathogens and their hosts interact. Lots of theory looks at just one pathogen and one host interacting with each other, and of course in the real world things are rarely that simple. As a very straightforward example, there might be a predator species that eats the host species, meaning that a pathogen unexpectedly dies out with the host species – you might not predict that outcome unless you considered the predator as well as the host and the pathogen. Ben is a mathematician, so he explores and explains these complex dynamics mainly through simulations and theory.

It’s relatively rare that we work with theoreticians, and it can be harder to find obvious ways in to the subject when there isn’t a single clear application for the research. What we do have is very clear primary and secondary messaging: firstly that hosts and parasites evolve together and affect each other, and secondly that evolution is random and not directed.

Ben is interested in having a physical installation that can be put, for example, in the foyer of his research building, the Milner Centre for Evolution in Bath (a part research – part education/outreach institution), or other exhibition spaces like the Eden Project, and also potentially used in schools. We’d like to think more about the intended locations and audiences for the final piece/s of work – schools have a lot of provision already, and science centres tend to attract people who are already sold on science.

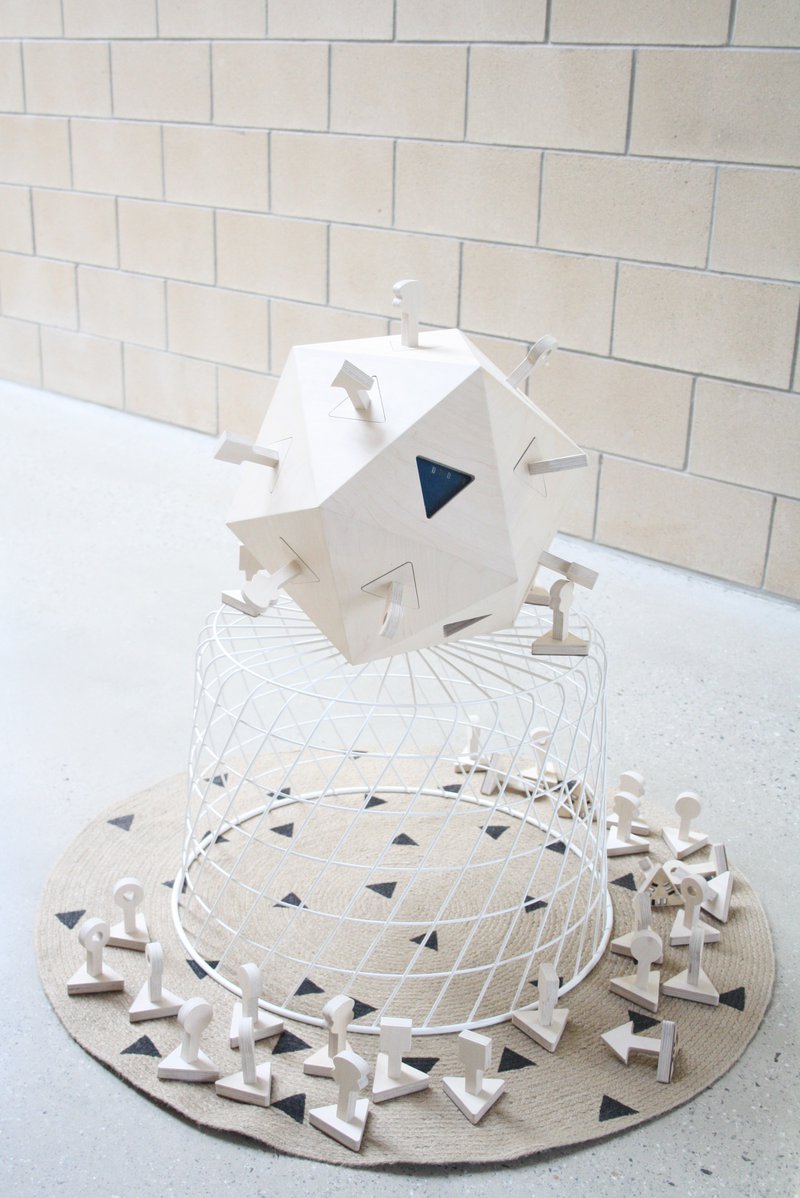

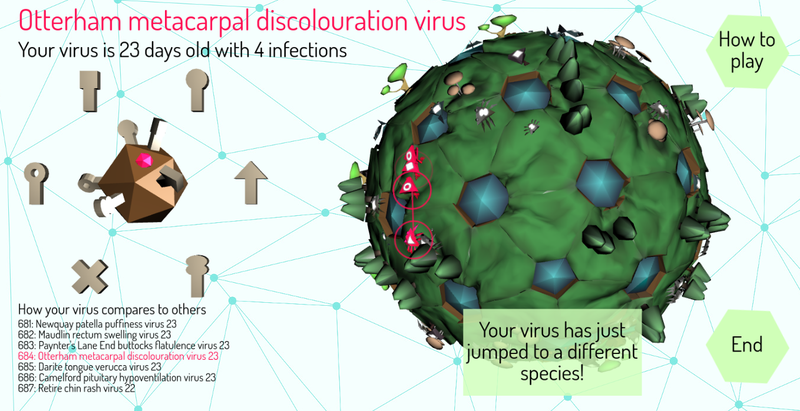

We’ve talked through lots of potential approaches in some depth, and Ben is keen to build on our recent and ongoing project Viruscraft (with another Ben who works on host-pathogen co-evolution – Dr. Ben Longdon). Viruscraft is a tangible interface in the form of a large wood virus, where the player can change shapes on the virus to ‘evolve’ it in a screen-based game world. The game world is inhabited by lots of different host creatures with corresponding shapes on them - the hosts either resist or get infected depending on how you evolve your virus. The aim is to keep your virus alive as long as possible by jumping into new host species, but making sure you don’t kill off too many hosts otherwise your virus will die off with them. The game is meant for installation/exhibition use – the tangibility means that people interact with it in more collaborative ways than how people typically use screen-based interfaces. A common dynamic has been gangs of children working together playing the game, with parents in the background having chats with the researchers on issues like vaccination, antibiotic resistance, technology design etc. Viruscraft was an R&D project where we worked as collaborators with Dr. Ben Longdon, funded by the Wellcome Trust. Working with Dr. Ben Ashby (yes this is confusing) gives us a chance to take the working prototype a bit further, and try to address some of the things that were a bit problematic.

Possible Viruscraft extensions include:

- Several multiplayer options: 1. Build a tangible host and have one person play the host and another play the pathogen 2. Have multiple hosts and multiple pathogens that can all be played, 3. Have multiple pathogens that play against each other or co-operate, with no control over the host.

- We could have part of the exhibit in different places, e.g. half in one school and half at another, so they can play against or with each other via a networked game.

- Make a very slow version that runs over weeks e.g. in schools, with people dipping in and out and working collaboratively, and a faster version for exhibition use.

- We could make mini virus electronic kits that people have to build first and then they can join the game (literally spreading viruses around the world).

One problem is that we haven’t yet had the opportunity to run full evaluation on the Viruscraft game and tangible interface – what are people actually learning or taking aways from it? Does the tangible version change how long people play or what they learn from it, compared with our equivalent online-only game version? We have a grant application in review at the moment with Ben Longdon to do this research.

One issue with Viruscraft is that it isn’t ideal for the second of our core messages – that evolution is random not directed – as you have to physically mutate the virus in order to play. It’s possible that some might interpret that as intelligent design rather than evolution, again this is something that we’d need to find out from interviewing players, and it is also something that will vary hugely between countries/cultures.

To begin with we’re going to:

- See if we can redesign Viruscraft to not have lots of small pieces that plug into the main virus shape. If we’re going to be leaving this in situ as an installation, we don’t want lots of tempting and easily-to-steal small pieces.

- Think about whether we can redesign Viruscraft to be a bit easier to make and maybe a bit lighter weight, with a view to open-sourcing the plans so other people can make their own, and making it a bit easier to set up. At the moment the design relies on access to a powerful CNC machine, and the purchase of an expensive custom-made angled CNC cutting drill bit. There will be some trade-off here, as at the moment the build is very robust, which is great when toddlers decide to use it as a climbing frame.

- Look at simplifying the screen-based game – at the moment it’s a bit confusing, with a spinning world covered in host creatures, and infections jumping between the hosts in a way that can be tricky to follow.

While we’re doing those things, we’ll be thinking about the possible extensions and deciding which direction to head in. We’re also interested in whether we should be grounding the project in a more real-life scenario (perhaps multiple scenarios) so that people understand the context a bit better. Some options include:

- Pollinator diseases, specifically the parasitic mite Varroa destructor and pathogens such as Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) that affect the honeybee. Varroa destructor is a vector for DWV that also increases the severity of disease, which shows the need to take a multi-species (community) view of the issue.

- Phage therapy, where viruses can be used to treat antibiotic resistant infections, and where we need to understand how the presence of multiple microbial species affects bacterial evolution to avoid making things worse. Phage therapy is touted as a possible replacement for antibiotics once those no longer work well - this is a major issue that very few people are aware of, and possibly the time would be well spent focussing on this as a context.

- A while ago we were contacted by someone who worked in infection control at the local hospital (Treliske in Cornwall), who was interested in an installation on flu and vaccination to demonstrate herd immunity - possibly there are also overlaps there, or at least a route to reaching people who could well be interested in the phage therapy case study.

So – it’s early stages in the project and there’s a lot to think about. If you have any insights, we’d be interested in hearing from you!