In 2025 we received funding from the University of Exeter's Civic University Agreements fund to re-design and test our air pollution sensor system SmogOff. Our priority was to make the design easier for people to replicate themselves, make some improvements on known issues with the previous version, and send it out to three community groups for testing. Another layer to this project was involving Dr. Jo Garrett to independently interview the participating groups before and after using their sensors, to see what we could learn about their motivations, experiences using the sensors, and understanding of the data.

This post is a write up of what we got up to, and what the outcomes were - we prefer to expose all the problems so that others can learn from it too, so we hope that is helpful.

Although there are loads of air pollution sensors out there (including open source ones like ours), we saw a few gaps which led us to start the project back in 2021 - firstly a need for sensors that were both relatively low cost but also calibrated to official government sensor stations (otherwise the data can't be used by communities to lobby their local councils), and secondly a desire for the data to be visible and open to people walking past the sensors in real-time. This second priority meant designing a stand-alone unit that could go on a lamp post or railing on the streets, and so it needed to be battery powered (which brings up some issues as you'll see later!).

The redesign of the sensor box is now fully documented, requiring only off-the-shelf components not bespoke parts as we had in our last version. We retained the same particulate matter, NOx and temperature sensors - we already had some misgivings about the NOx sensors, which are notoriously tricky to work with (probably the reason that hardly anyone uses them in their projects). We chose to keep them in because for some specific applications the data can still be useful, and the particulate matter sensors are reliable enough to sense-check any spurious NOx data.

Our first major hurdle with this project was that although we had Cornwall Council on board throughout, it turned out that since we last calibrated SmogOff to their sensors, all (yes all!) their air pollution sensors had either been de-commissioned or were broken with no date planned for fixing them. A bit of a shock. This meant that we had to rely on our previously calibrated version 1 SmogOff sensors to calibrate the new version, which isn't ideal at all. This also meant we were restricted in how much we could change, as we needed to maintain the same process of data collection that had been previously calibrated.

The new sensor design ready to be shipped, together with a spare battery and charger to allow one battery to be charged while the other is in use, meaning little loss of data during the times when the battery needed changing over:

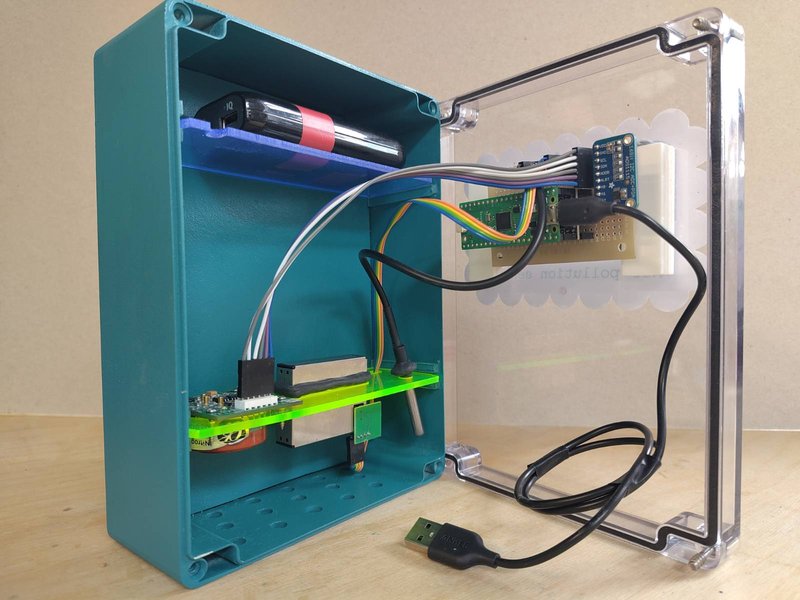

The inside of the sensor box, showing a shelf at the top for the battery, a shelf at the bottom (just over the air holes) to house the particulate matter, NOx and temperature sensors, and the screen on the front of the box. The need for the screen to show the data still means it is a bit awkward to open the box for battery changes, as the cables need to remain attached, but it is still far easier than the previous design:

We finished the build of the three boxes and shipped them out in June - they went to Clean Air Whalley Range in Manchester (an air pollution awareness group), Bike Worcester (a cycling advocacy group), and Lanner Parish Council in Cornwall. Each of these groups had contacted us about using our previous version of SmogOff, but we'd held off until we found the funding to improve the design and work properly with them. The groups were each written into the funding bid which allowed us to pay them for their time on the project and also provide a budget for them to run any events or buy any extra things they needed for participating (like locks to secure the sensor where they wanted).

In their interviews at the start of the project, the community groups talked about their motivations for taking part - these included current data limitations; to share data and engage the community; a desire to lobby for action; to gather evidence and data; specific concerns about air pollution; and a desire to help with the development of the sensor. You can also read about the interview analysis in more detail, written by Dr. Jo Garrett.

We ran an initial online training session on how to use the sensors, and provided ongoing technical support throughout. This involved trouble shooting when there were issues and also the presentation of the results. The participants had initial concerns over their own skills (predominantly around the technical aspects), the time commitment for battery changes (which needed doing daily), whether their community would be supportive, and whether the sensor boxes might be vandalised. We did our best to support the skills side of things, and to reassure that it would be no problem if the boxes were stolen or broken as that was part of the experiment - we were actively interested in whether that would actually happen or not!

One of the most notable outcomes from our perspective was that the participants tended to be overly cautious about where they located their sensors, mounting them high up so people couldn't see them, or in private gardens for example. This was simply due to caution and concern over theft/vandalism, however it negated the purpose of having a screen so passers by could see the data, and also likely led to much lower pollution readings than expected. Air pollution is extremely variable over very short distances (even a metre or two), so sensors really need to be located exactly where people might be experiencing the pollution - for example at a bus stop on the edge of a road and at body-height. In hindsight, we wonder if the concern for the sensors might have been caused by the participants being updated about the design and build process as we were doing it - maybe if they hadn't known how much time went into them they wouldn't have felt so protective! If that's true, it would be an interesting flip-side to being fully open about the process of what's involved.

We also found quite a big mismatch between the intended use of the sensors and how people wanted to be able to use them. They were designed for short term use, e.g. 7 days in one location, perhaps repeated twice for confidence in the data, or a few days in several locations to compare levels. Our funding bid was written with this type of use in mind in terms of the length of time of support that would be needed. However two groups wanted to use them for a lot longer, over several months, which led to fatigue over the daily battery changes and a lot more unfunded support time than anticipated. We also had a consistent frustrating problem across all three boxes where the rubber seal around the lid failed, indicating a manufacturing problem by the company we bought the boxes from - with the boxes costing £60 each, this was a bit painful. This is a crucial element of the design as it provides waterproofing in the rain. It is an easy one to fix in future as we would just need to find better boxes - this is not an issue we've experienced previously with our Sonic Kayaks which have a similar design.

Another possible issue is the screen - at the moment it is designed to cycle between 3 screens, firstly one saying who made it and what it is (to hopefully alleviate concerns if people see it and wonder what it is), secondly showing the pollution data in realtime as numbers, and thirdly a smiley/neutral/unhappy face as a summary (as the numerical data is only easy to understand if you know what you are looking for). We picked a paperwhite screen as screens are power-hungry and these are less so, allowing a longer battery life and fewer battery changes - however the way these screens work is that to show anything different (even just the numbers changing) requires a refresh meaning the screen looks blank for a second. This caused some concern with one participant as they didn't like it looking blank briefly. The screen does seem like it retains importance though, as the same participant liked the fact that it drew people in and helped start conversations.

One very notable thing that happened was a mismatch between people's expectations and the actual data collected, which apparently is common for air pollution projects. We found a distrust in the data because the values were low, and that people were really hoping for higher numbers, even though in reality low values are a good thing!

We tried to reassure participants that they were working by suggesting lighting/blowing out a match nearby to see the values rise. We also talked about how the values would typically be much higher indoors than outdoors (indoor air pollution is typically a much bigger health problem, from cooking in particular). In future we would re-iterate early on in these projects how much the sensor location matters (council sensors are usually right by the side of busy roads).

From our combined experience on other projects, readings can be counter intuitive to begin with, for example we've seen very high levels in rural areas caused by walking through the smoke from a single wood burner in someone's house, in a park caused by a food stall, and on just one street in a city that was full of restaurants. During our tests of our sensors we've also seen dramatically different results at the front and back of a building.

We did rack our brains for anything that might cause low values and double/triple check everything, particularly as this is a new design, but with one participant placing their sensor well and getting clear evidence of rush hour peaks and troughs, another participant saying their data matched the previous council data, and the particulate and NOx sensors broadly in agreement in all cases, we feel we can have confidence in the design. The air flow into the box could be compromised by how it is mounted, or it could simply be lower due to the new design, however this would only lead to smoother data (as the fluctuations in pollution levels in the air it reads would be slower) not lower numbers.

We produced a final data report for each community, which introduced the sensor and produced summary graphs that showed the average recorded levels and the World Health Organisation 24 hour limit. In general, the report was perceived as useful and presented relevant information.

This is Jo's summary based on her interviews:

Overall, the use of the SmogOff sensor was shaped by a complex mix of motivations, enabling factors, and practical barriers. Participants were driven by a desire to address gaps in existing air quality data, engage their communities, and support the development of an open, accessible sensing tool.

Use of the sensor enabled meaningful engagement in one case, and, in another, provided reassurance where results aligned with previous monitoring. However, participants also encountered practical challenges with the device, including maintenance demands, durability issues, and display limitations. Crucially, when the recorded data did not match expectations or existing sources, this generated doubts about accuracy, reducing trust and willingness to share the results.

What we'd change next time:

- Use a different box to house the whole thing in, because of the seals breaking on all three.

- Probably ditch the NOx sensor as it's a cause of a lot of problems and doesn't add a great deal.

- Really try to hammer home from the start that the sensors can be treated as disposable, so people feel more ok about placing them in appropriate locations.

- Have a specific section of the initial training about how to locate the boxes, and why the location matters so much, including very general information on known patterns of air pollution and how they can be counter intuitive.

- Have a council that is properly funded and cares about environmental issues, so they maintain their air sensors and we can calibrate to them! The participants were made aware of this, and we suggested calibrating against their councils' sensors if at all possible.

- We could think about a solar charging system to reduce battery changes, but this adds more cost and more complications for the users as they'd need to keep an eye on it rather than just getting into a regular habit of changing the battery.