In April, we held our second Viruscraft workshop to begin testing a game and tangible interface that we are making together with evolutionary biologist Dr. Ben Longdon.

The Viruscraft project is about finding new ways to understand how viruses evolve to jump between different host species (like bird flu moving into humans). The project launched in 2017 with a workshop bringing crafts experts together with biologists to decide which of the various virology and evolutionary concepts to focus on, and to begin to prototype some game ideas. In 1962, Caspar and Klug published a theory of virus structure proposing that ‘spherical’ viruses were constructed from identical geometric subunits. Caspar and Klug’s work explicitly referenced the geodesic domes made by architect and designer Buckminster Fuller. This concept of geometric viral structures was appealing to our participants, and so became a core aspect of the project. The second concept that resonated with the participants was the structural aspect to how viruses attach to, and ultimately get into host cells. In biology, the way this happens is is often referred to as a ‘lock and key’ mechanism. The host cells are coated with small proteins called receptors, which are essentially equivalent to locks. Viruses are coated with similar proteins (the keys), and these need to match the host receptors in order for the virus to get into the cell. To be able to infect a new host, the virus needs to evolve the shapes on its coat to match those on the cells of the new host. Similarly, to become resistant to a virus, the host needs to evolve to change the shapes coating its own cells so that the virus shapes no longer match. And so, and arms race begins where the hosts are constantly evolving their receptor shapes to try to evade virus infections, and viruses are constantly evolving their own shapes to try to infect enough hosts to ensure their own survival.

In our prototype game, there is a planet which is inhabited by various host species – on their backs there are shapes which refer to the host’s receptors. There is an icosohedral virus (a ‘spherical’ shape made from 20 triangles) which begins with no protein shapes on its surface. The player chooses shapes to coat their virus, and can continue to change these shapes at any point, evolving their virus. The player needs to match the shapes on their virus to those on the hosts – being careful not to become too good at infecting one type of host as that will kill off the host entirely, meaning that the virus also dies out. To survive, the virus needs to evolve to jump between different hosts, and maintain infection at a manageable level to keep some hosts alive. You can try out various prototypes here.

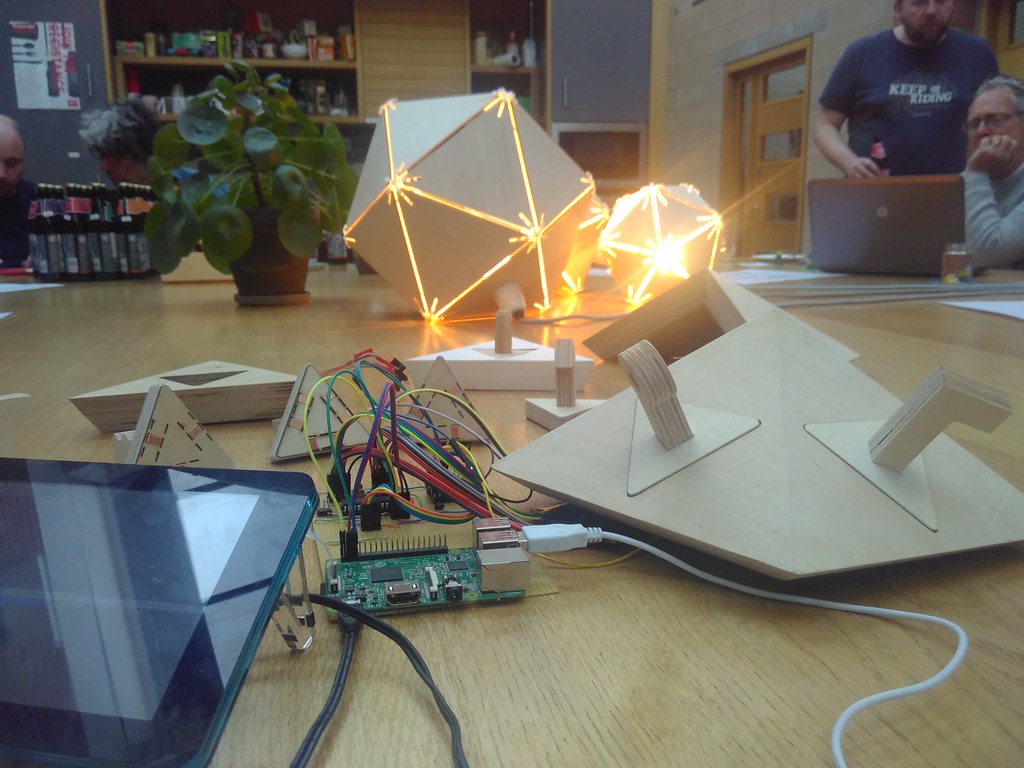

As well as a screen based game, we are building a tangible interface. This is a wood virus shape, together with smaller wood pieces that plug into the virus surface. The shape of the pieces that plug in is automatically detected, and as such the tangible interface can be used to play the game instead of ‘evolving’ the virus on the screen.

For the game testing workshop, we set a mixed group loose on the screen-based system and the tangible interface – providing little by way of instructions, to see what people intuitively understood. We’ll be using the feedback gathered to improve the system over the coming months, before making the final installation. Below are the main changes that we will be making:

Screen-based game modifications

- Providing prompts/popups through the game so people understand more about how the virus and hosts interact.

- Add additional ways to modify the game world before beginning – at the moment the sea level can be changed which influences the number of different sea/land species - we may also include a slider for land fragmentation which would influence how likely it is for hosts to meet each other (include pop-up to explain what will change). We also plan to include a slider to determine the host diversity at the start of the game, and the virulence (nastiness) of the virus.

- Start the game with only one species, to help people understand the game dynamics early on.

- Make the different species look more distinct from each other.

- Visualise transmission events between hosts (transmission occurs when hosts come into close contact, and when their receptor shapes allow the current virus to infect both hosts).

- Make the game competitive by including a leader board, including how long your virus has survived, how many host jumps you’ve made etc.

- Look at possibilities for graphical representations of success measurements.

- Fix so that when the virus dies out, the game stops completely with a hard reset.

- Fix world connectivity issues – currently land species go in the sea, and sea species can swim under the land!

- Add a clear-all button to the virus to remove all receptors.

Tangible interface modifications

- At the moment the shapes are recognised by a different pattern of copper strips on each shape which make connections in a circuit on the main virus structure. This approach is not very reliable as the shapes need to be pressed in hard, and held in place in order to make the connections. In the final installation there will be 10-15 holes for shapes to plug into, so people will not be able to press all the pieces in at the same time. We are switching to a new system where we use reflective photo interrupters instead. These components have a light that shines out, and a sensor which detects how much light is reflected back – if something black is put above the component, less light is reflected back to the sensor than if something white is put above it. Using this system, we can put different colour patterns on the base of the plug-in wood pieces in order to detect which shape has been plugged into the virus.

Once we have made the necessary modifications, we will announce the final Viruscraft event date for anyone to come and try the game out. To receive updates about events from the FoAM Kernow studio, you can join our events mailing list here.

Viruscraft is funded by the Wellcome Trust.