Back in 2019 we took part in the Algomech Festival, performing may pole dances with woven robots at the Wintergarden in Sheffield’s city centre alongside livecoding and ancient Greek poetry reciting. A lot has changed in the world since then, and the plants in the Wintergarden have grown into full size trees over the intervening years. Many of the plants growing there originate in South America, protected from the elements in their urban location. As we wandered around before setting up for the 2025 Alpaca Festival, Paola Torres Núñez del Prado recognised some plants that grow in her families garden in Peru, which made it the perfect setting to bring a taste of Andean technological thought to the people passing by and sheltering from the rain outside.

This was our first public test of the pluggable knots programming woven robots setup - a textile based technology stack. We also experimented with Paola’s new computer vision system for knot recognition, she’s using this to sonify the labour theory of the Inca civilisation by comparing values that the knots represent. The main taxation system of the Inca was labour, and you paid “tax” by donating a proportion of your work time to the society and in return were provided with a safety net if times became bad. All this information was recorded in knots - the knots represented the “debt” you had to your local group, known as your ‘ayllu’ and by extension the entire society. While taxation methods have changed, many of these social structures are still very much in use in the Andes today.

This small takeover of the Wintergarden turned out to be an effective way to talk about some of these issues, as the robots attracted children and gave space to talk about Andean society with the parents. Those with a deeper interest (such as festival participants, and quite a few passers-by) could get more involved, experimenting with the knot sonification or playing with the knots to change what the robots were doing.

Setup

We had a large table with the knot programming interface, a set of phones running Paola’s computer vision software, a laptop showing images of Andean culture and khipu information along with general background material about the festival as context.

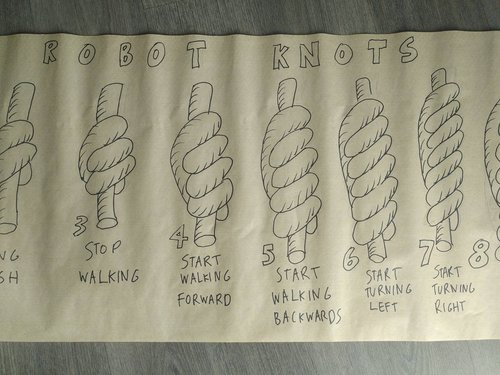

We had 8 robots (with 2 spare) spread out on the floor in front of the table - these are not the same ones we had before, which now live in the Deutches Museum in Munich, but a ‘second generation’ built for Alex’s Algorithmic Pattern project. With the robots on the floor were a set of cushions and big sheet of paper with hand drawn knots explaining what each one represented, both as a number (the same system used by the Inca), and as an instruction for the robots (walk forward, turn left, speed up, flash LED, etc).

The knots plug in to each other to form an upside down tree structure which itself plugs into a “main pendant” at the top, which provides power, and is communicating with the robots via radio messages. Each location along the main pendant represents a different robot, and as the knot structure is changed the robot is sent a new program to run based on the knots used. This is quite interesting as you can for example “copy-paste” code by unplugging an entire knot program from a robot and plug it into another one to see the same program run on it. The central idea here is that there is no screen required to do any of this, and each knot also provides tactile feedback via a vibrating motor - so it prioritises material understandings with touch, and de-prioritises any sense of what we know as knowledge work - screens, keyboards, large amounts of words and symbols.

As soon as we started setting up we were surrounded by inquisitive children. “What do these robots do?” “Why are you doing this?” “What are robots for?”, I tried to answer these questions as well as I could but they were displaying a critical view on technology that is sadly completely absent from our industry or media.

What people did

I think the fact that we had various levels of activity possible was an advantage over what we have tried like this in the past (either with the robots previously, or the pattern matrix before them). People’s activities ranged from:

- Looking from a distance

- Talking with us about things

- Playing with (picking up, helping) the robots

- Talking about the knots and how they relate to what they are doing

- Looking at the knot interface

- Listening to the knot sonification

- Operating the knot sonification themselves

- Changing a few knots and see what happened

- Programming a robot and seeing how they could make it move in different ways

The main thing that wasn’t as obvious to me as it was immediately as we set up, was the separation between the knots and the robots. Being distant on a table meant that it took a certain level of confidence to play with them that the robots don’t require.

Technical issues

The knots worked fine, despite some “manufacturing inconsistencies”, some of the early PCBs are machined by CNC while others are professionally made, and the plug attachment varies quite a lot as it’s soldered directly on the board in a slightly random orientation. We are also stretching the technical limitations of the i2c communication protocol in absurd ways, but all of this worked fairly well with no failures (with around 20 knots in use).

Probably to be expected as the robots have been used a lot, but these were OK being handled by people and kept on working - we had one robot with drooping back legs due to a stitching failure (actually, ironically a loose knot) where one of the servos is enclosed in the weave.

Part of the thinking behind this design is to have plenty of redundancy - the knots, robots, and connections on the pendant are replicated, swappable and independent of each other. This turned out to be important as the main pendant had issues with the connections - the place where the cables connect to the PCB is problematic, mainly due to to the cable having earth grounded shield which you can’t crimp well. I’d tried soldering this to a compatible wire but that added more fragility, so I think the solution to this might just be larger connectors than the ‘industry standard’ ones.

I connected the Raspberry Pi Pico that compiles the knots and sends out the radio messages to my laptop under the table so I could easily debug anything. The problem with this is that I needed to restart it twice, I think it’s more stable if it’s running standalone.

The other issue we had was simply determining which robot was being programmed. We have a lot of little numbered flags that can be attached to the robots which I should have brought, as once they get all mixed up it’s very had to tell which one is which. The solution was unplug whatever it was running temporarily and use the “short flash” knot on its own, and see which one stopped moving and responded.

Future ideas

To a certain extent the direction we take this will depend greatly on the context in which we use it next. We’ve generally designed them to be used more in classroom settings, perhaps with people with sight loss rather than in open public settings like this, but if we continue to use the knots and robots together - we need to think about how to situate the knots in the same space as the robots.

- Can we use multiple ‘main pendants’ - so you carry your khipu over to your chosen robot and it sends it to it based on proximity (perhaps using infra-red or audio communication rather than radio)?

- Could they somehow connect directly to the robots - plug them in to program, or even drag them around? They’d have to be much smaller, and optimising code would have different motivations!

We can also create music with the knots - this could work via Paola’s sonification, or using a live coding based musical pattern, as Alex has done before with the pluggable knots - where he used solenoids hit objects to create rhythms.

How do we better integrate ideas of social structure/labour value in the Inca world - this topic is a rich one, and starts to directly connect with the politics and history of the Andes. This may be one way to realise our long term aim for the project, which is how to contribute back to the khipu-using societies that exist today.