Invisible Worlds Residencies were developed in 2018 as a collaboration between FoAM and the Eden Project, to explore phenomena beyond our senses: too vast, too small, too fast, too slow or too far away in space or time. The residencies were funded by the Wellcome Trust and Arts Council England as part of the Eden Project's Invisible Worlds exhibition.

We received an exceptional mix of submissions representing a very wide range of arts and scientific backgrounds, with applicants from all but one of the continents. Three residencies were selected, with a mix of approaches including fermentation and genomics, ceramics and geology, and sound art. The residencies took place from July to October 2018. The residents each wrote a final piece, and these are presented below as a celebration of their work.

Ferment!

Hoon Kim, Elizabeth Fortnum and Sean Meaden

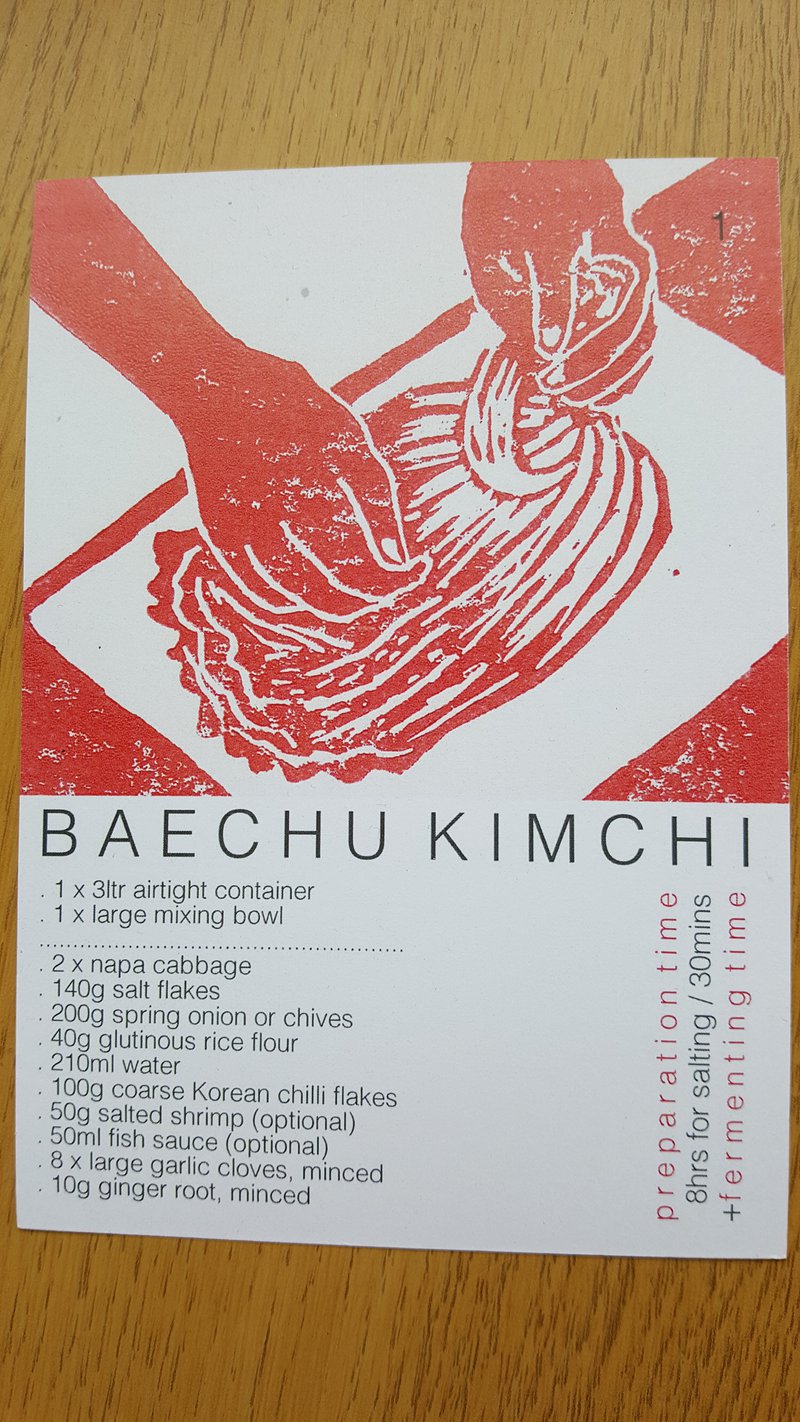

Our residency proposal was to expose the Eden Project visitors to the world of fermentation through science, food and creative illustrations. We hoped to make fermentation more accessible to a wider audience and explore its benefits to the individual and societal health. Using nanopore technology, we were able to isolate the DNA of our in-lab ferments and create real time snapshots of their microbiomes. Collaborating with the Eden horticultural team and storytellers, we showed through daily workshops how to turn excess or otherwise wasted parts of vegetables into delicious and healthy ferments. We created visually beautiful recipe cards and are continuing to process the data creatively to imagine the invisible world of ferments.

We spoke to the visitors almost daily and perhaps in this endeavour found the most satisfaction and inspiration. It was clear that many people were interested in fermentation with regards to health, sometimes even specific personal ailments. Many had introduced fermented products into their daily diet and some into their cooking. As a response, we decided to create a small reading list of reliable academic papers as well as give some advice on how to judge the credibility of a research so that people could pursue their own lines of enquiry.

We found that most hadn't considered fermentation's role in reducing waste or improving the health of our environment. We showed how to make kimchi and other simple ferments from abundant autumn and winter produce harvested from the global gardens as well as how to use wasted parts of vegetables such as sweet potato vines, bean leaves or garlic stems. We considered that in this way, fermentation's ancient role in preserving should still hold a place in society.

As our research progressed, we became interested in the idea that “everything is everywhere, but the environment selects”. This is known as the Baas Becking hypothesis and states that all types of bacteria are able to disperse everywhere but only thrive when the environment is right. We took samples of a radish kimchi 6 hours into fermentation as well as its raw components. The lactobacillus was present in the ferment sample but could not be found in any of the original ingredients. This suggested that the lactobacillus was either present in alternate sources, such as the chef's hands, or were present in such low levels that they could not be detected. We were keen to pursue this enquiry further but ran out of time.

Ironically, we consider that a lack of time was our main limitation. As a group of professionals who hadn't previously worked together pursuing an open ended residency, we found that the bulk of our enquiry took shape towards the end of our two week stay, by which time we weren't able to carry out any experiments. However, the technology is available and we are writing a short academic paper from our brief time together, and hope to continue updating the audience through our blog of scientific discoveries, reliable and enlightening papers, translated recipes and creative interpretations of the invisible world of fermentation.

All of our data can be found here and you can read more about the residency here.

Disintegrated Rock

Rosanna Martin

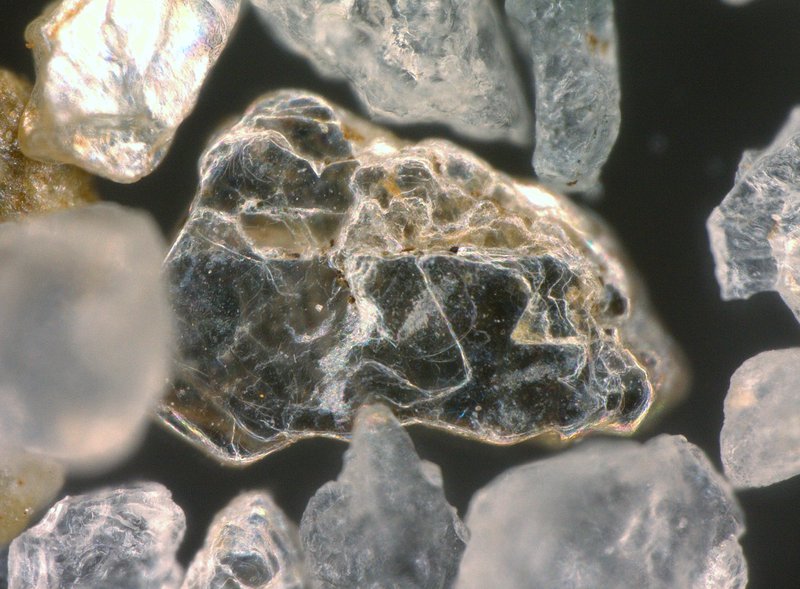

Sands, silts, clays and other unknown waste materials collected on walks across Cornwall’s Clay Country were the starting point for the first phase of my residency at Eden. I was interested in looking at geological samples that had been displaced or changed due to the industry in the area. I walked around quarries, up spoil heaps, along river beds and on beaches, in search of samples that had come to be in that place due to human activity. I spent five days looking at my samples under the microscope in the laboratory at Eden, with support and insights from the lab technicians. I was able to take digital images to record what I was seeing. Clay; its properties, potentials and limitations, has always fascinated me, and it was a completely new experience to be able to look at it in its raw form at such a high level of magnification.

After this initial phase of research, I wanted to make work in response to what I had seen that would then be taken to the Eden Project for the visitors to view and interact with. The experience of looking at all the samples had been completely spellbinding to me and I decided to make a series of samples that visitors could look at under the microscopes in the public lab.

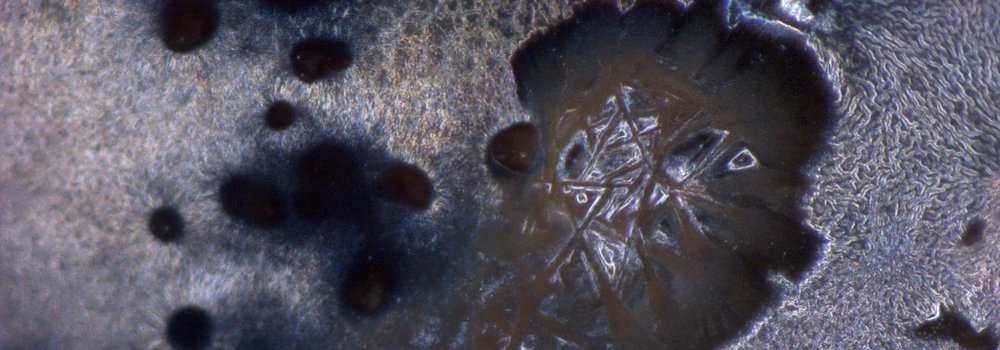

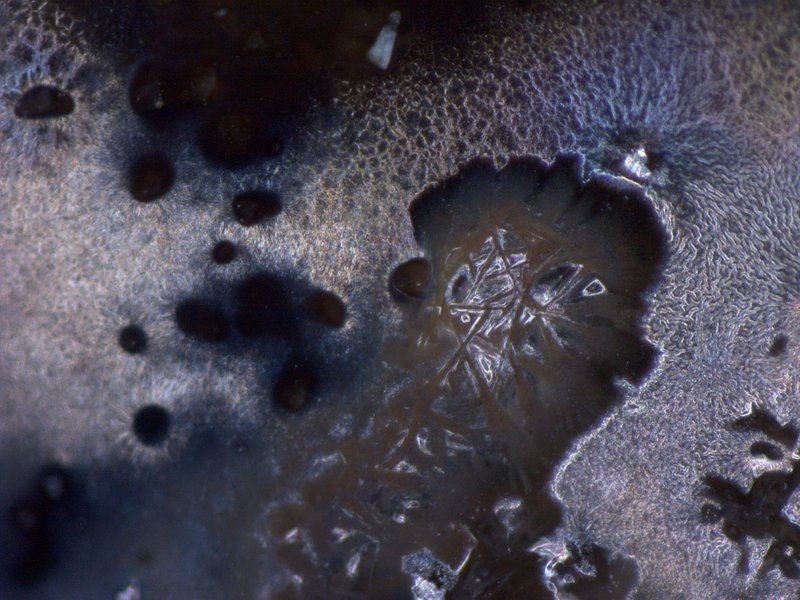

Using clay collected from the river edge at Par Beach, combined with porcelain, I created a series of flat discs, cut out to fit within the lab’s Petri dishes. These discs were all bisque fired to 1000C, onto which I used the material samples I had collected in the first stage to make small compositions in combination with glazes, which were then refired to 1280C to fuse all the materials together. I was interested to see how one material changes from its raw state to when fired, and how visible this is to the naked eye and under the microscope.

The discs were taken to Eden, categorised and laid out for visitors to look at alongside the usual samples of butterflies and bugs. I was also able to spend more time looking at the samples, and took more images which were displayed on a large screen in the lab. The visuals from these samples were even more extraordinary than those I took of the raw samples, suggesting the surface of other planets or galactic skies.

The residency has given me a richer understanding of the materials I use, inspiring a sense of wonder at their geological formation, and has offered new areas of exploration within my practice. I have recently shown some slides of the images I took in an exhibition at Grays Wharf and I am hoping to use them to inform and inspire a new body of larger work next year.

Spending time in a laboratory was a new experience for me, and I became increasingly interested in the processes involved in scientific classification; many of the samples that I collected were hard to identify due to being created as a by-product from smelting processes. The microscope I was able to use was incredible, and yet there was always a bit of something that you couldn't fully see, and as such the process of looking was completely addictive. I'm hoping to further explore these grey areas, of unknown materials, unseen places, and our desire to categorise the world in the next work I make.

You can see more of Rosanna Martin's work here.

...and then we see if we will be friends

Till Bovermann and Katharina Hauke

Friendly Organisms … and then we see if we will be friends is an art-science project exploring ambivalent sites and their systemic interplay with their environment using sound and other means.

In September 2018, Katharina and Till set out for a four-week long expedition to Eden Project in Cornwall, UK. Our intention has been to invite (non-)human beings on the site to create electronic sounds as a shared artistic intervention. But we soon found that we were confronted with something much more than just a place to make music at: Eden Project presented itself as a giant, living, and pulsating organism. So complex, so lively, that most of its aspects continuously escaped our comprehension. As these impressions slowly settled in our thoughts and work, we deliberately extended our invitation to the organism called Eden Project itself.

But how to make it aware of us? How to approach an organism consisting of structures as large and complex that we could stroll inside it without even noticing, lest comprehending, that those structures are part of, that we are are part of it?

When arriving, we tried to answer questions like "Does the official intention of Eden Project justify its existence?" or "Despite its official slogan, what does Eden Project really contribute for the bettering of the (direct or distant) environment and its future?". The more we discovered the more these questions shifted towards: "Does *our* intention justify our existence (here)?" and "Who are we to judge?"

We developed and studied several methods, all of them based on, and most of them involving the act of listening.

Examining through listening

For the majority of the first week, we set out with microphones, sound recorders and cameras to observe and take in. We went to places both accessible to visitors as well as hidden from their ears. We listened to the inaudible, and consulted Eden staff members for their stories and got rewarded by very personal takes on why they are part of Eden Project.

Playing along

Soon after the first week, we altered our strategy for being in the field. Instead of pure listening, we used our technical equipment to add our own sounds to the places we found. It again shifted our perspective.

Exploring the context

We spiraled outwards into the environment of the organism that is Eden Project, climbed the coasts and explored similarities between Eden Project and Cornwall's cultural as well as its engineering heritage.

Visualising

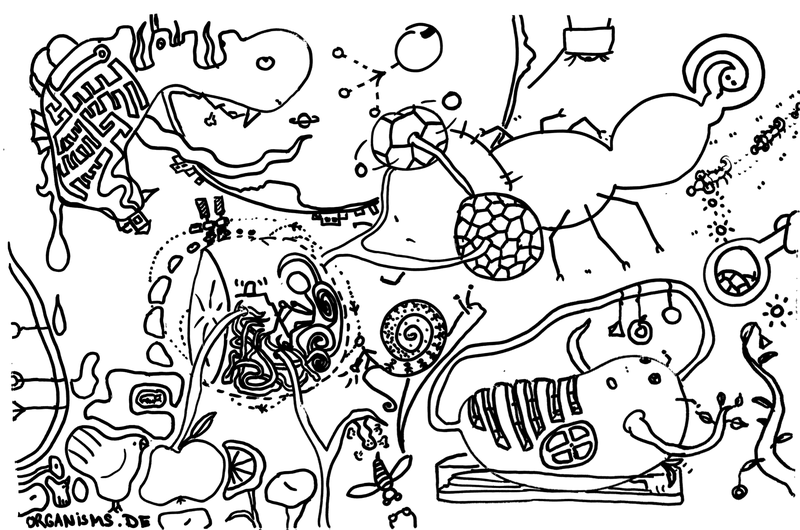

Throughout our exploration we made attempts to visualise the organism that is Eden Project as it appeared to us. Silently taking turns in drawing on a whiteboard revealed subconsciously formed concepts and ideas about the organism called Eden Project and served as a key component for our continuous discussions.

Presenting

Opportunities to present our work where aplenty. Apart from talking to lots of people about our residency and its activities, we not only had the chance to visit FoAM Kernow for their annual get-together, but also to be part of two arts weekends within Eden Project: One being a lesson to be learned, one successful in a more direct interpretation of the word.

A path emerges

After four weeks, we concluded that, due to the sheer complexity of the organism that is Eden Project and its interwovenness with its surroundings, it is impossible for us to answer our initial questions. But maybe we can raise awareness of those facets of Eden Project that we found interesting and worth to tell about. Hopefully, for some, they will turn from amusing anecdotes into projects worth being explored in depth and in the best case being communicated to an audience — be it within or between departments of Eden Project, to school children, or the general public.