Last week we launched our Sonic Kayaks for the first time at the British Science Festival in Swansea. Sonic Kayaks are scientific instruments for citizen-led marine microclimate data collection, as well as musical instruments for expanding our senses allowing exploration of the underwater environment in real-time through sound.

The installation ran over two days, and was fully booked with 64 participants. This blog forms our documentation of the practical lessons from the event.

Media -

In the run up to the festival, the project received quite a bit of press attention – we had a long interview with Cerys Matthews on BBC Radio 6 Music, another on BBC Radio Wales, BBC World Service, and coverage in the local print media - in a couple of weeks Sky News are coming to film the kayaks in Cornwall. The combination of sound art, climate and marine science, and sport seemed to be the appeal – and the attention was made possible by the British Science Association pushing the project via their established press routes.

Funding -

Funding for the Sonic Kayak development came from the British Science Association and FEAST Cornwall – both are very forward thinking organisations who are not afraid to merge disciplines or to take risks on non-standard projects. The major UK arts funders deemed the project too light on 'public engagement' and the Welsh launch location too 'international', and there are no appropriate science or interdisciplinary funding streams. The project highlights the disconnect between what people find inspiring (as represented by the media coverage and bookings), and the remits of the older science and arts funding organisations in the UK. We look forward to a post-disciplinary world. Now we are planning to develop the prototype incrementally as people discover their uses for it.

Build Design -

Version 1 of the Sonic Kayak kit consists of a bunch of electronics (GPS, Raspberry Pi, pre-amp, battery) in a central box, with speakers on either side in tubs topped with 3D printed gramophone-style horns. Cables needed to go between the central box and the speakers, and sensors (digital thermometers and hydrophone) from the central box into the water. The three main components (box and two speakers) were linked with metal loops, and strapped onto the boat with webbing – using thick neoprene cushioning. The design was to enable the kit to fit any standard kayak model, and to be secure enough not to fall off even in the event of the boat capsizing.

We knew the design was splash-proof but not waterproof – on the first day of the event the conditions were kind to us and the kit kept running for four hours straight. On the second day, strong cross-shore winds and ground-swell meant that the first group of paddlers lost control, with five capsizing within minutes of hitting the water. Remarkably, no equipment was lost, which gives us a nice (albeit painful) test of the build design.

If we want to take the kit on the sea again, we need to look more thoroughly at waterproofing. Both the Minirig speakers and the Raspberry Pi computers that were submerged had instant corrosion on the parts with voltage differentials. Despite a thorough soaking, after drying and cleaning, they all recovered. Some options to think about are using resin to cover the electronics, and hermetically sealing the cable ports.

Towards the end of the day we had condensation inside the main electronics box, caused by the components heating up inside, surrounded by a colder environment outside the box. Improving the waterproofing would no doubt help, by reducing the flow of humid air into the boxes.

A full post on how to build a Sonic Kayak will follow soon. In the meantime, the software is available here, the 3D print horn design is available here, and a basic schematic of the electronics is available here.

Sound Design -

In the installation we used three layers of sound:

1. Data from two digital thermometers on each boat was sonified in real-time. As the temperature goes up the pitch goes up, and vice-versa, with no sound when the temperature is stable.

2. A hydrophone to transmit live underwater sounds.

3. Geographical locations were mapped with sounds attributed to them, using software designed for Sonic Bikes. The GPS on the kayaks detected when the boat was within one of these zones, triggering the sounds to play. We mapped three bands of sound running out from the shore, to allow for the tide changing dramatically during the sessions (Swansea Bay has the longest tidal range in Europe). One zone had poetry about climate change and the sea, another zone had music, and the third zone had electronic voices with factual messages about climate change.

During testing in the estuary next to our studio, the hydrophone gave insight into man-made noise pollution particularly from boat motors, and noises from wildlife and the motion of the water. In Swansea Bay the environment is much more homogenous (endless sand) and noisy above water (waves) – the hydrophone contributed very little in this setting, so having the additional GPS triggered sounds proved an important addition.

Running the Event -

The event was run with great help from the 360 Beach and Watersports centre – our host Ashley was hugely competent, taking each group of kayakers out and being responsible for their safety on the water. We would not want to run an event like this alone. For future installations we will always look to collaborate in this way with a local watersports centre.

We took a pop-up tent and solar panel for storing, fixing and charging equipment – this proved critical in the great-capsizing-event of day two.

One lesson for the future is to have a backup plan in place in case of total failure. When the conditions were rough on the second day, the 360 centre host called off the event on the grounds of safety. While we were rescuing the submerged kit, we had to come up with a plan on the fly. In the end we talked participants through the equipment, recorded hydrophone sounds in the waves, and went Sonic Beach Walking instead, as the kit works just as well on land as in water.

A final lesson is to stick to single day events – this project is demanding physical work, on top of the usual pressures of running an installation or workshop.

Paddlers' Feedback -

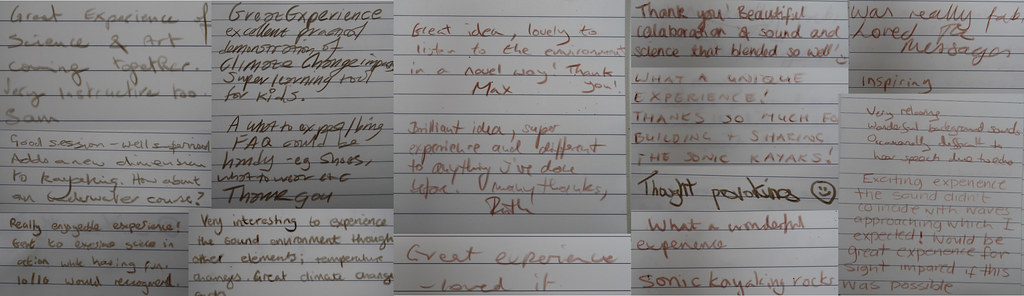

We are waiting on the summary of the formal evaluation forms from the British Science Festival, and will update this post when they come in. We had comments books ready for when the paddlers emerged from the water - we didn't catch everybody, but the image below shows the complete and unedited written feedback.

Two points were particularly interesting – firstly that the majority of the participants understood the climate change aspect to the project – and secondly that two participants mentioned that the concept would be particularly good for visually impaired people.

The Data -

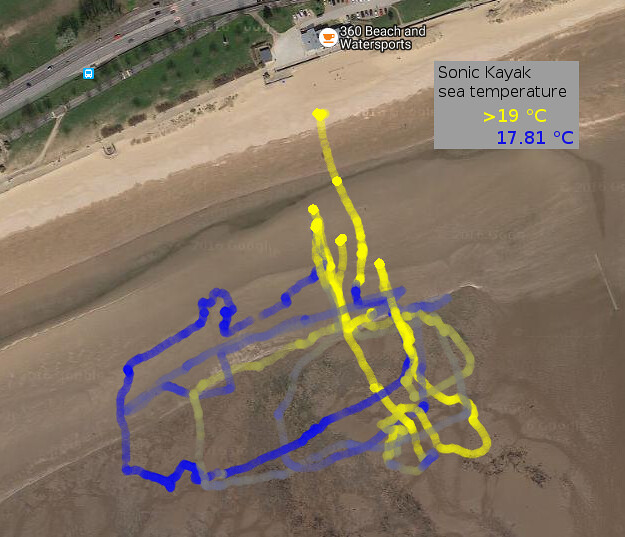

We uploaded the data to Github immediately after the event. Below you can see the data collected by the participants, mapped over a satellite image. Each map is from one of the two Sonic Kayaks, which took roughly the same routes, indicating that one challenge has been met - the data is replicable. On each map the four trips have been overlayed. It is possible to see where the boats were taken out of the water between trips (the yellow regions where the temperature rapidly goes up), and how with successive participant groups as the tide moves out, the water temperature increases – showing how the kayaks can be used to detect spatial and temporal microclimatic changes.