I've been playing with a weaving pattern over the last few months, it's based on one of the oldest pieces of fabric found, in Hallstatt in Austria. The papers and publications on it are largely pay-walled and quite tricky to get hold of, but with a bit looking around, I managed to recreate the whole pattern - consisting of a whopping 72 instructions for 13 tablets.

After warping the loom, a bit of simulation and some going backwards and forwards I managed to weave the pattern through once, and then took the still warped loom and everything with me on the train to a workshop in Manchester as a demonstration of a more complicated weave and then left it for a few months. Coming back to it I had a record of where I stopped, but the tablets were in a mess from travel, and I wasn't entirely sure what was going on. This must have been quite a normal situation to weavers, no matter when they lived - but I'm going to go through this process in detail and then explain a bit more why I find this interesting at the end.

My first approach was to try to un-weave to a place I thought was I knew was correct and restart from where I thought I was in the pattern, based on what it looked like compared to the simulation. I also thought I could use the border weave (which is simpler) to try and get locked in to the right place but this didn't really work at all, the problem is you start off again and have to undo the wrong bit, and each time it makes it more difficult to know if you've stopped in the right place.

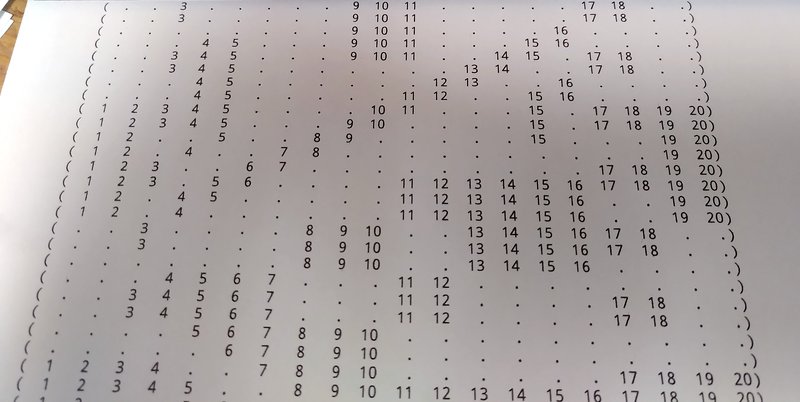

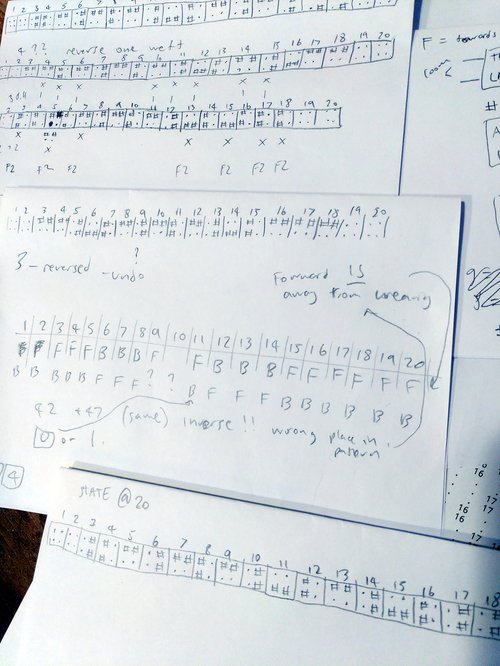

The next approach I used was to use the yarn colour positions in each tablet to figure out where I was. The idea was that this could provide an absolute position given the 'state' of the tablets. In order to do this I had to read off each tablet and record it on a bit of paper, and I adapted a script I've been working on to generate the instructions for hand weaving to output the tablet state after each step of rotating forwards and backwards. This didn't work either, and I'm not entirely sure why - I ended up searching the whole pattern for candidates measured by distance and found some in places that I knew were wrong with a few cards different. I think this as partly but not entirely due to something that I discovered in the course of this that I suspected previously, that the pattern on the simulation is upside down (it's showing the reverse of the weave, but I guess that's subjective!).

The third attempt was to only un-weave a single step (I'd removed quite a lot of the good pattern by this point) and record direction of tablets I needed to rotate to un-weave to the previous weft. I could then reverse the directions to find what the instruction was that I'd previously followed - I could use the same code I'd used to search for the instruction line that matched in the pattern, and this indeed finally worked, I could reweave the pattern I'd un-woven and continue, the pattern looking like nothing had happened.

So the things this involved:

- Written instructions for each step (as well as the warping of the tablets).

- A simulation to check the pattern visually.

- Taking copious notes on bits of paper when it went wrong.

- Algorithms to visualise and search the states of the tablets and the instructions.

The Hallstatt finds were so important that historians have named their ancient society after it - the 'Hallstatt Culture' which existed from 1200 to 450BC. We don't know what they called themselves, what language they spoke, or really very much about them except these kinds of archaeological finds. They are defined as being on the cusp of being a prehistoric culture (techically I think 'proto-historic') because while written language perhaps existed in the area towards the end of their time, we don't really know if they used it - and if they did, it probably wasn't well spread through their society.

So we have no idea how they recorded these patterns - which are far more complex and lengthy than later tablet weaves made by the Vikings for example - did they have a way to do it verbally, or through songs?

They may have been pre-writing - but they certainly weren't pre-algorithmic. These sets of binary instructions are the definition of an algorithm. For me, in 2025 - unpicking this problem required using tools that weren't available at the time, pencils and paper, let along software and source code. What techniques did they use to manipulate and understand the algorithms they created? As we grapple with the realities and failures of AI and accelerationism, there are a lot of things missing in the way our culture understands its relationship to our algorithms - I wonder what they could teach us.

I'm using this repository to keep track of this work, and I'm hoping to get some of these debugging tools into the tablet weaving language which is running here.